On this page

The stuff of everyday student life isn’t often thought of when considering Harvard’s impressive history. But for a group of high school students visiting the Harvard University Archives in July, the materials that helped them connect most with the past were those that captured “ordinary” life on campus.

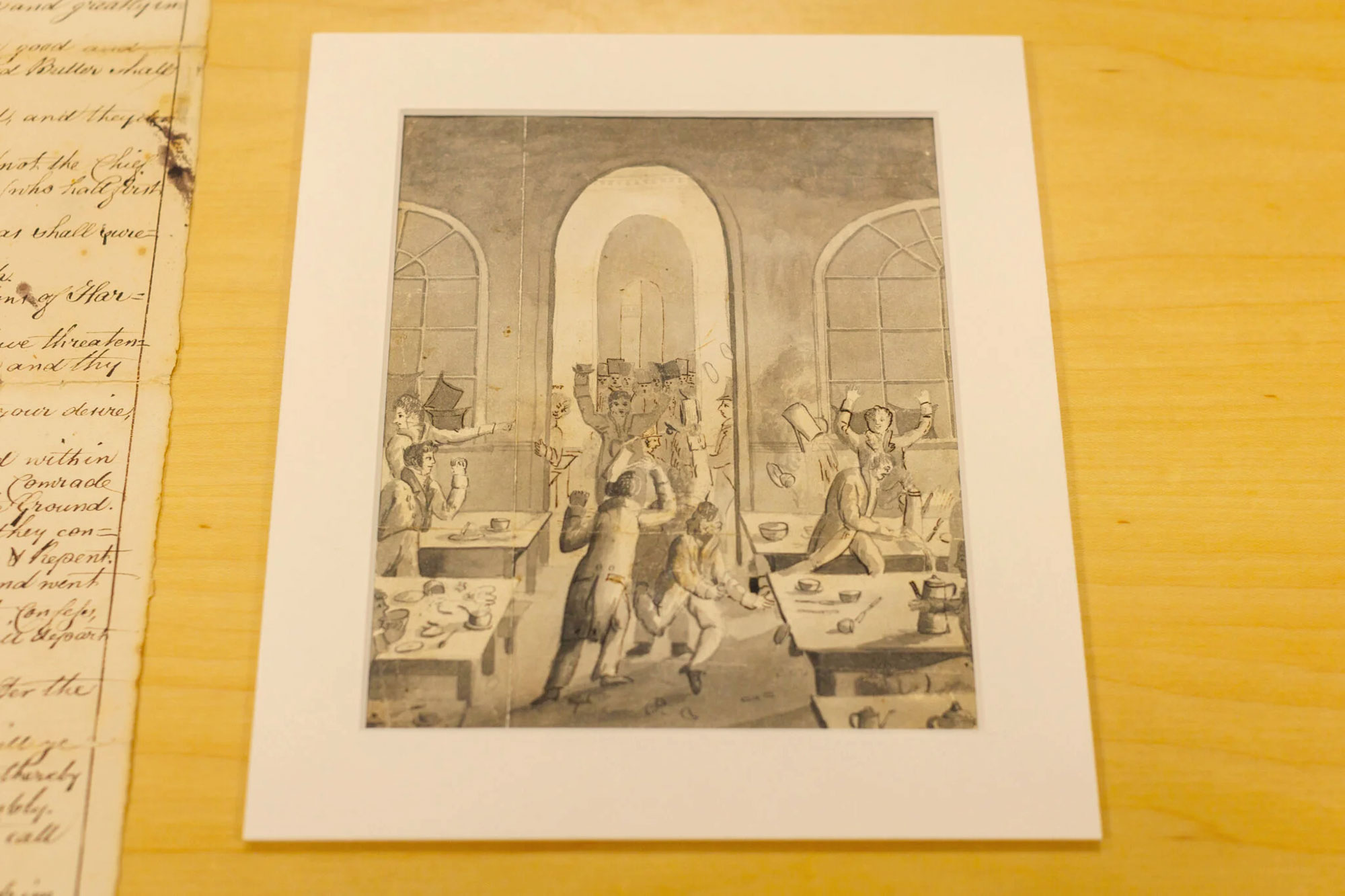

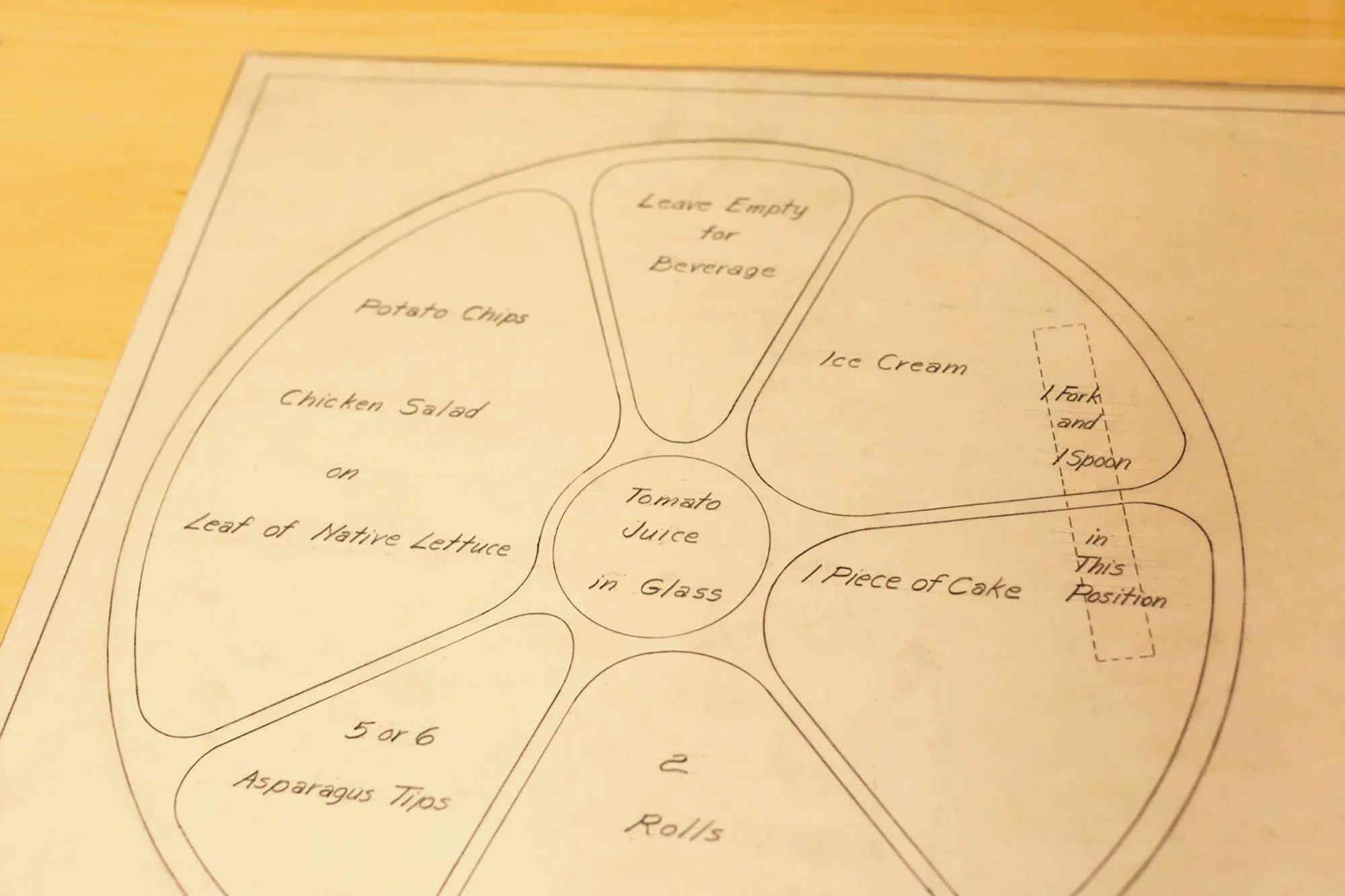

They read a student’s 1969 journal that juxtaposed accounts of a Civil Rights protest with descriptions of birds he saw out his window. They laughed at an illustration of a food fight in a dining hall in the 1700s, sparked by spoiled butter. They examined the photo of a Delphic Club party circa 1950s. There was a menu listing 17-cent meals from 1909 and a math homework assignment from 1795; photos of classrooms and dorm rooms from the 1950s; a Harvard Camera Club membership certificate from the 1890s; and a copy of the Kirkland House “facebook” from 2003-2004.

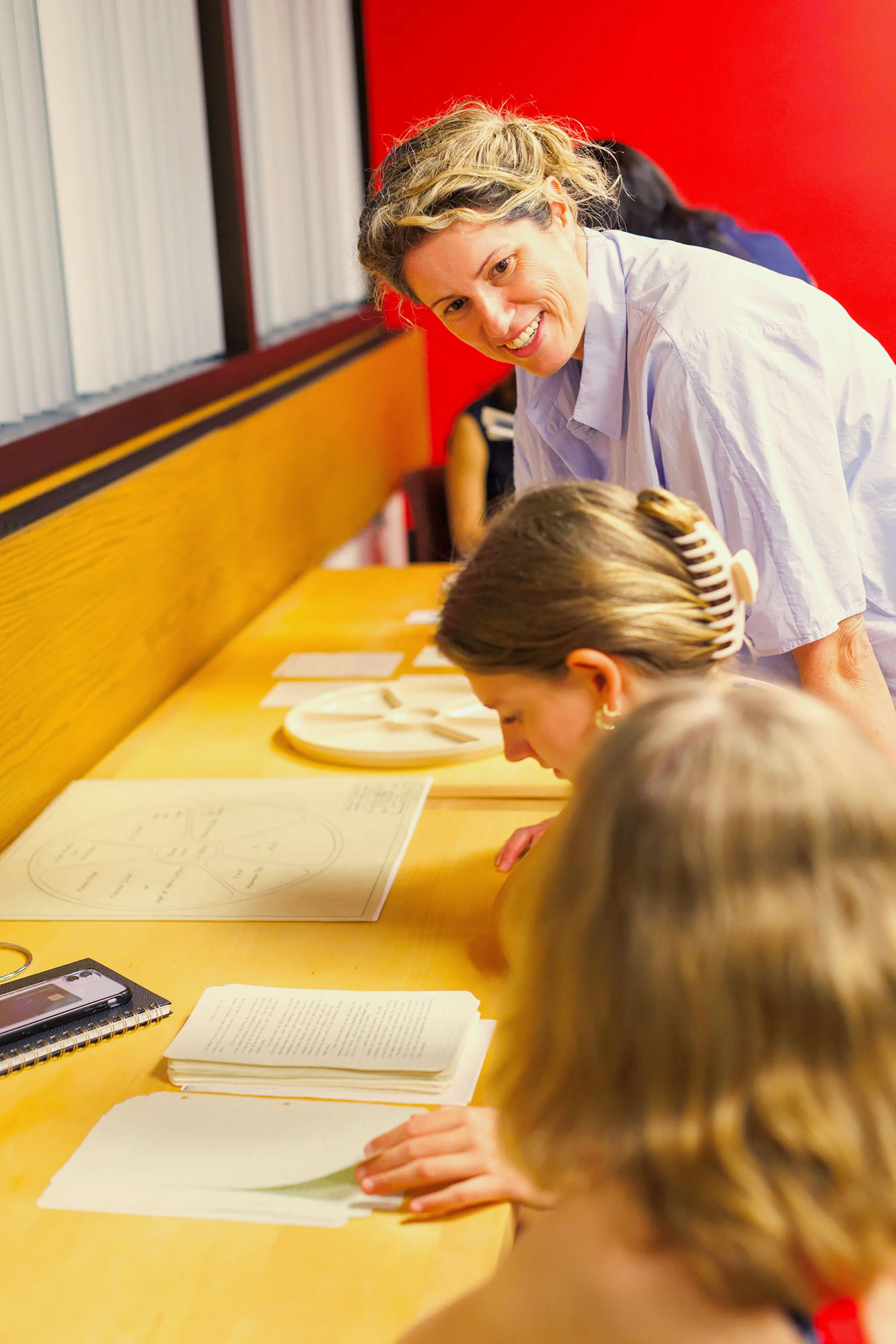

Archivists Jehan Sinclair and Juliana Kuipers worked with Division of Continuing Education instructor Chloe Chapin to compile a diverse array of materials from throughout Harvard’s history. They sought to “illustrate the College experience,” Sinclair explained, for high school students who will soon head to college themselves.

“People think of Harvard mainly as really rigorous academically, and it is,” Sinclair said, “but it’s not just that. Life at Harvard also means going to parties, hanging out with friends, joining extracurricular activities, and participating in activism.”

The group visited the University Archives this summer for Chapin’s Anthropology course “The Stuff of Life,” part of DCE’s Pre-College Summer Program geared to high school students ages 16-18. Each student enrolls in a two-week course intended to give him or her a feel for college-level work, as well as attending social events and co-curricular activities.

Zoe Schnadower inspects slides on a light table; Chloe Chapin engages with students.

“The goal of this class is sort of the opposite of trying to teach students a discipline,” Chapin said. “I’m trying to expose them to as many different disciplines as possible through archival materials.”

During this year’s two-week course, Chapin’s class visited the Widener, Houghton, and Schlesinger libraries, as well as the Harvard Map Collection, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology.

The trip to the Archives, though, was particularly relevant to her students’ lives.

“The archivists and I did a lot of brainstorming to think about what would be useful for high school students to see,” Chapin said. “Their worries about the future are ‘What is college going to be like?’ and ‘Who am I going to be in the world?’ I wanted to find materials in the collections that spoke to those questions, as much as I could.”

The students were particularly drawn to materials like the food fight illustration and mid-20th century party photo, that showed young people at College having fun and being irreverent.

“They really loved that stuff,” Chapin said. “They told me they didn’t realize people in the past were also silly.”

She added that one student, inspired by the University Archives materials, even did their final project for the course on the concept of “silliness.”

Some students observed that youthful hobbies and passions have changed over the years, but the sensibility of teenagers from decades or centuries ago was very similar to the modern day.

As one student put it, “These are all just young people like us, figuring themselves out.”

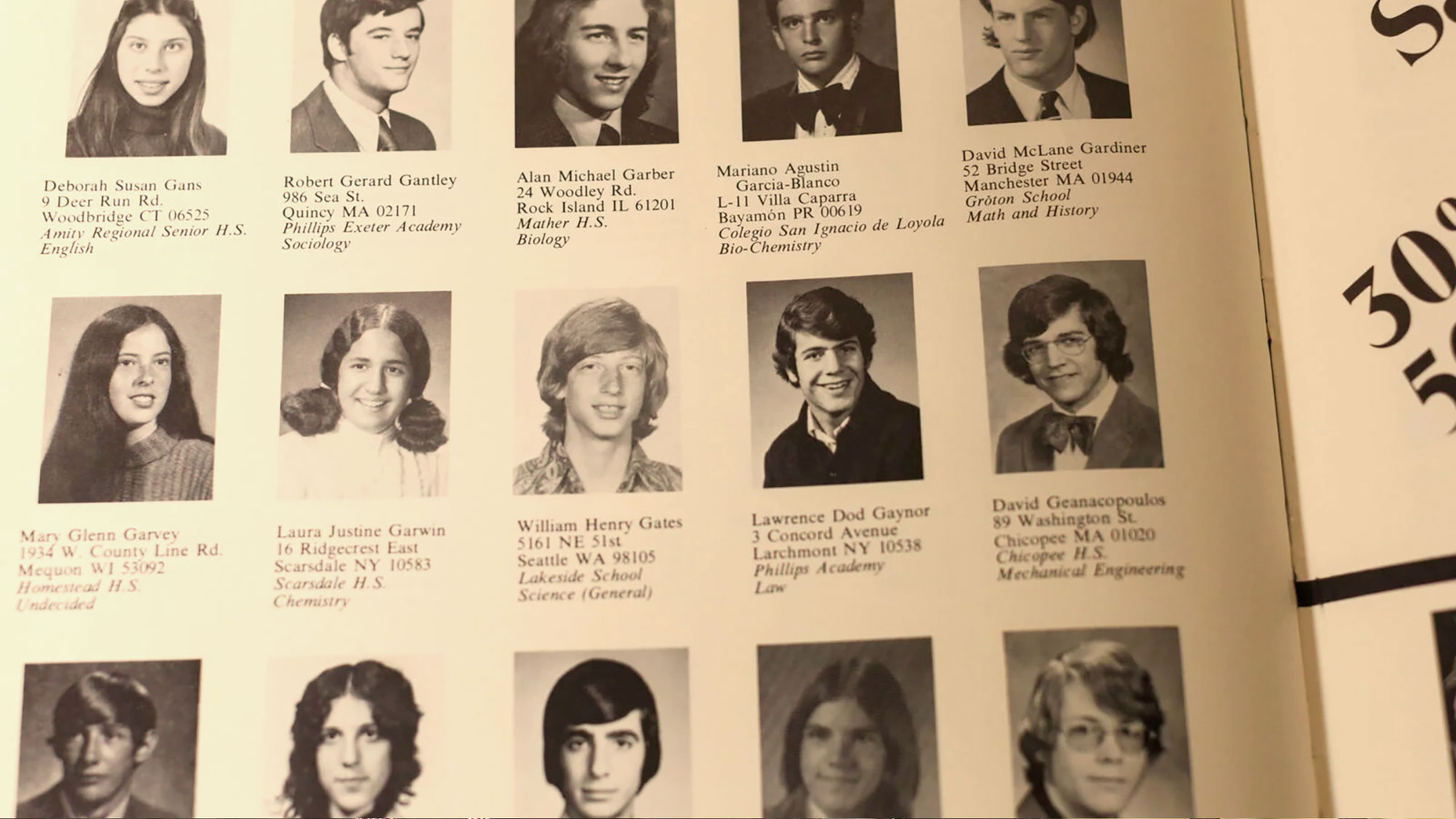

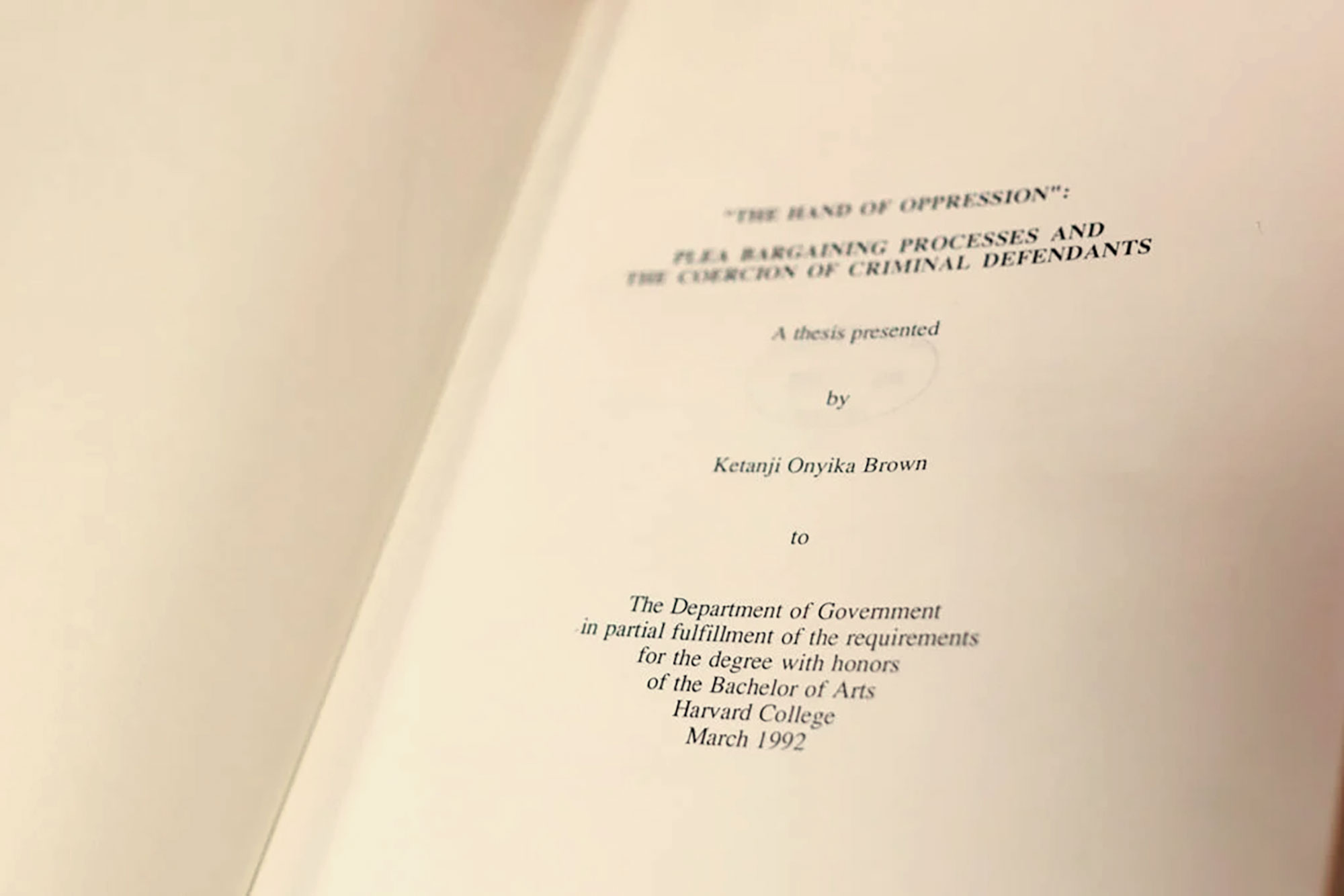

Some of the materials were tied to names the students recognized, including Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s undergraduate thesis, a photo of John F. Kennedy as a student, and a piece of homework by future scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois. They could even flip through a printout of code written by Bill Gates and Paul Allen in 1975 that, Sinclair explained, became the basis for Microsoft’s first product, Altair BASIC.

There was a novelty to seeing work created by people who, as one student said, “went on to make a mark on the world.”

Acknowledging this, though, led him and his classmates to reflect on the significance of materials related to students whose names are not well-known. A firsthand description of a University-wide protest, just because it was written by someone with no name recognition, isn’t any less fascinating to read. In fact, as another student observed, archives from “regular” people are more precious in some ways, because “there’s no way to Google them,” and the archives are the only piece of their story we have.

“During the rest of the course, students often referred back to the material they encountered in the University Archives with that idea in mind,” Chapin said. “Our visit really laid the groundwork for these students’ own possibility, that the work College students do can be both ordinary and extraordinary.”

This was part of what Sinclair hoped the class took away from their visit — the same way that student journal entries from the late 1700s are now valuable primary sources, the routine of an “average student” today could help future historians shed light on the year 2023.

“I hope they can see how archives relate to their daily lives,” she said. “And how the things they create today could become archives tomorrow.”

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell. Reprinted with permission from the Harvard Gazette.