History is often brought to life through icons. And Harvard has amassed plenty in its 375-year history. Symbols connect present and past and shape our sense of Harvard in powerful ways.

Some of these icons, like the John Harvard statue, are famous and cherished. Some, like the color magenta (move over crimson!), had their defining moment long ago. Each icon is an opportunity. Together, they reveal how members of the Harvard community created their institution within shifting historical and social contexts.

Below are three examples that made Harvard what it is—and was.

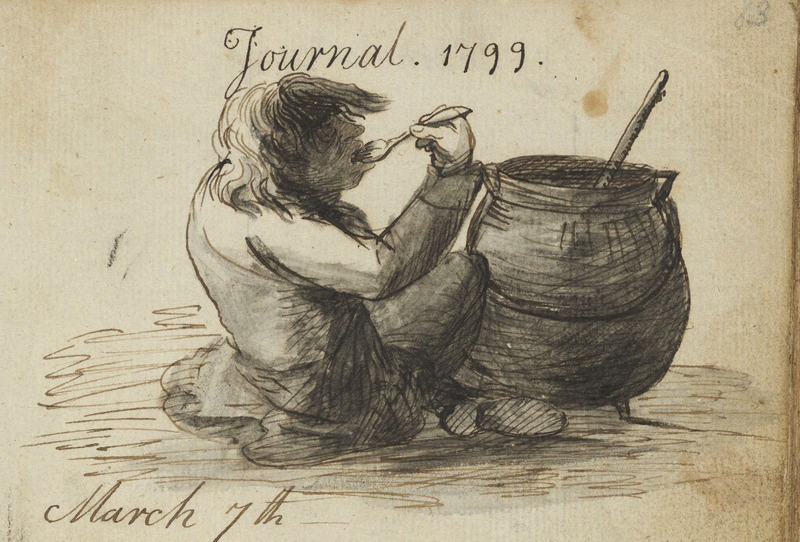

The Hasty Pudding Pot

Today, mention of the Hasty Pudding evokes images of college men in fabulous drag costumes, performing satirical routines or roasting the Woman or Man of the Year, who clasps a golden Pudding Pot award.

Before 1795, however, “hasty pudding” brought to mind only a slow-cooked mixture of cornmeal, butter, and molasses: a distinctly American take on the classic English pudding. That year, 21 Harvard students founded a secret society to (according to their minutes) “cherish the feelings of friendship and patriotism,” stipulating that “members in alphabetical order shall provide a pot of hasty pudding for every meeting.”

They idolized George Washington and engaged in debates, oratorical challenges, and mock trials. Hasty Pudding theatricals were born, with some controversy, at a surprise opera performance in 1844. Harvard was still an all-male academy, so club members played women in their first production.

The cross-dressing tradition continues today. The exuberant burlesque of today’s shows is some distance from the formal oratory of 1795. And the Pudding Pot itself has transformed from a symbol of collegial filiopiety to one of theatrical absurdity and achievement.

The Veritas Shield

Veritas: truth. A simple, commanding ideal blazoned across the Harvard coat of arms. The veritas mottosimultaneously invokes the highest ideals of scholarship, citizenship, and spiritual purpose.

The heraldic shield seems as old as Harvard itself. But it was repeatedly lost and reformed as the institutional mission shifted over the centuries. The Board of Overseers devised the original at a meeting in December 1643, ordering “there shall be a Colledge seale in forme following.” The first official seal, known from a 1650 impression, kept the books but already discarded the guiding motto.

Veritas would not return for 200 years. University President Josiah Quincy reintroduced something like the original sketch at Harvard’s 1836 bicentennial. In doing so, he legitimized his vision for Harvard’s future by referencing its past.

Today, the omnipresent veritas shield functions in a similar way, symbolizing the university’s authority, standards, and brand.

Printing type

The worn lead printing bars in the accompanying photograph, no more than 2.5 cm long, connect early Harvard to the most transformative forces of the colonial world: empire, literacy, and religious inculcation.

They are pieces of seventeenth-century printing type, which archaeologists excavated from Harvard Yard. Skilled printers used this type to create the first books printed in British North America.

Harvard’s first president, Henry Dunster, acquired a press through marriage. The technology legitimized the school in its most precarious years, allowing leaders to control knowledge as they created it.

Printing type symbolizes another history as well: Native American. After 1655, Dunster moved his press to the new Indian College, built to educate Native American youth alongside English in knowledge and Godliness.

Missionary John Eliot used the early press to print books for native conversion, many of which—including the first Bible printed in the British colonies—were in the Algonquian language. Some excavated type matches these books. Native American scholars used Harvard, literacy, and Christianity to forge a new place for their communities within a shifting world.

Harvard history and beyond

These Harvard icons are three of many at work every day. As you walk around campus or hear the latest University news, be alert and you will recognize more.