On this page

As a student, you’re asked to learn a lot on a given day, and to not only retain that information to pass the course, but to use that information to build your knowledge base and future career. Yet it can often be a challenge to retain what you’ve learned — especially if you don’t yet know which approach to learning is best for you.

The good news is that there’s no one “right” way to study and retain information. But being a better learner requires some effort to ensure what you’re learning is engaging, personal, and multi-sensory.

To learn more, we spoke with Dr. Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, an educational researcher who teaches “The Neuroscience of Learning” at Harvard Summer School, about how various active learning techniques can help you better retain the information you learn in class.

Meet Our Expert

Tracey is an instructor at the Harvard University Extension School and Summer School, where she teaches The Neuroscience of Learning: An Introduction to Mind, Brain, Health and Education.

Learn more about Tracey

She is an associate editor of Nature Partner Journal Science of Learning, and is a former member of the OECD expert panel to redefine teachers’ new pedagogical knowledge thanks to contributions from technology and neuroscience.

She is co-founder of Conexiones: The Learning Sciences Platform, which provides evidence-based resources for teachers in Spanish and English. She has taught Kindergarten through University, and now works closely with the Global Science of Learning Network, the International Mind, Brain, and Education Society, the American Educational Research Association’s Special Interest Group on Brain, Neurosciences, and Education, and the UNESCO Chair for Education and Neuroscience.

Her research focuses on the integration of Mind, Brain, and Education science into teachers’ daily practice and professional development; transdisciplinary thinking; curriculum changes to enhance math and literacy skills; bilingualism and multilingualism; and the leveraging of technology to enhance learning outcomes. Her most recent books are Writing, Thinking, and the Brain, the first book on the neuroscience of writing; Questions Kids Ask About Their Own Brains, a response to 400 of the most common questions about the bran; and Bringing the Neuroscience of Learning to Online Teaching which shares 40 interventions that work equally well online as in person.

Originally from Berkeley, California, she has lived and worked professionally in Tokyo, Lima, Boston, New York, Geneva, and currently in Washington, D.C., where she works with teachers, schools, governments, and NGOs in 40 different countries.

Here are some insights and advice on how to become a better learner and create strategies and environments that work best for you.

Rethinking Your Approach to Learning Retention

When it comes to retaining something you learn in class, the question becomes two-fold, says Tokuhama-Espinosa: “How do you make the information meaningful and get it into your brain? How do you get it back out in a new context?”

She adds that the ultimate litmus test of learning is using the information in a new context, not just performing it within a classroom setting, such as remembering information or vocabulary to simply perform well on a test.

Instead, being able to retain what you learn starts with “a long-term attitudinal shift about self-investment and self-critique of [your] own learning,” she says.

Tokuhama-Espinosa emphasizes a more effective approach to learning that is rooted in the Ancient Greek concept of “Know thyself.” She recommends examining your lifestyle and habits to find strengths and weaknesses to better optimize your learning retention.

“You know yourself well enough to know what you need right now. Do you just need more sleep? Or do you need to keep reading? Do you need to eat better? Or do you need to work with friends?” she asks. “It’s looking at long-term [adjustments]. How can you change your basic habits about approaching learning across your life?”

Your brain would love to learn through all of your senses. The more input, the better.

Dr. Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa

How to Take a Multi-Sensory Learning Approach

According to Johns Hopkins, when we learn something new, we form connections between neurons in the brain, which create new circuits between nerve cells and “remap” the brain. The more the brain is exposed to the information, action, or event, the stronger the connection. This is why the more you practice something, the better you get at it.

However, the idea that everyone has one specific learning style that’s best for them — visual, auditory, reading, or kinesthetic, often referred to as VARK — is no longer supported by today’s educational community. Instead, it’s about taking a multi-sensory approach.

“Your brain would love to learn through all of your senses,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “The more input, the better. In fact, learning the same conceptual understanding through multiple senses is great because it reinforces slightly different neural pathways in your brain.”

In other words, instead of creating one road to access knowledge, you’re creating multiple roads for more access avenues. Diversifying these pathways helps to reinforce information in multiple ways, ultimately improving recall.

The multi-sensory learning experience

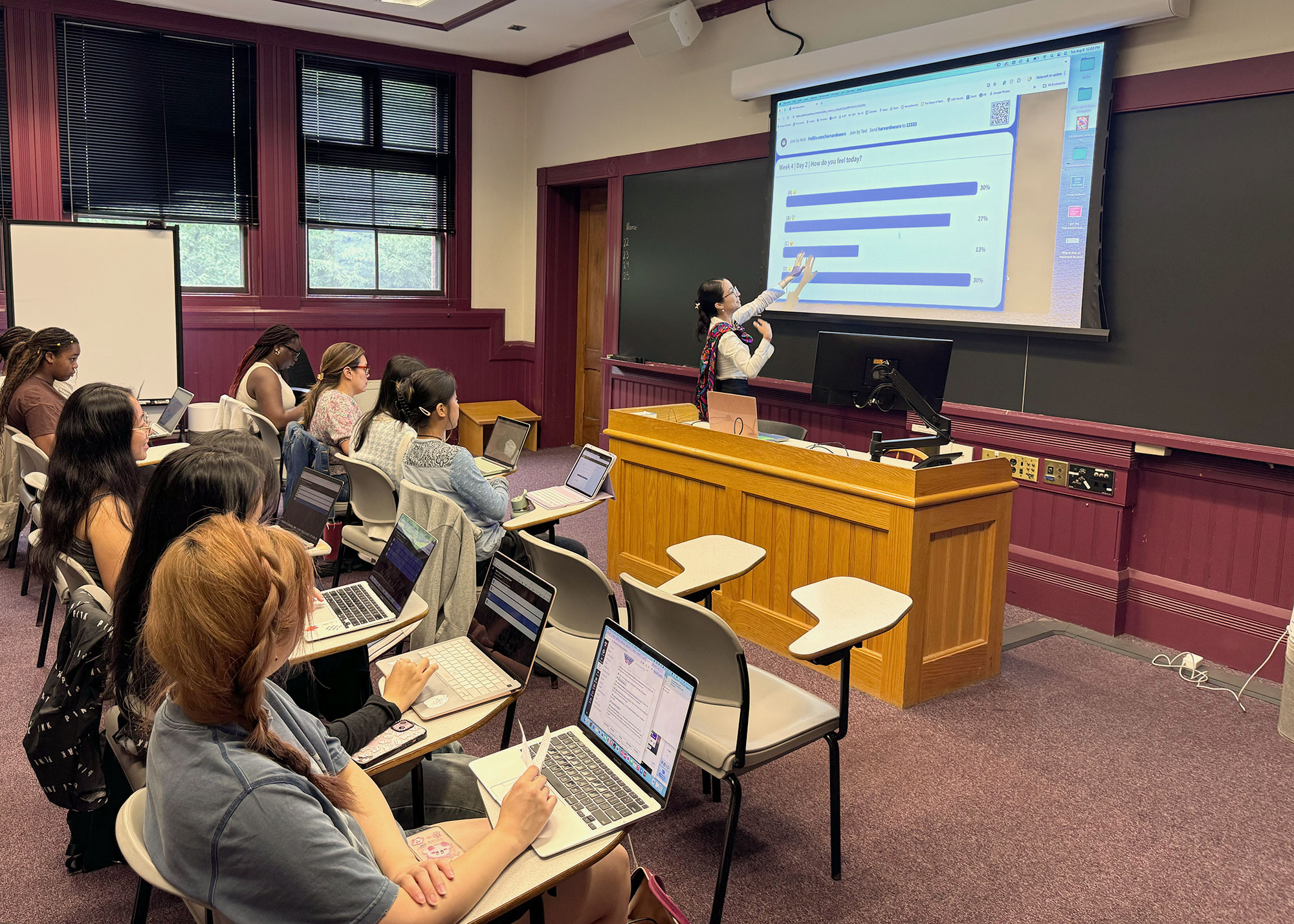

To give students the best opportunities to learn, a teacher may structure their classroom with multi-sensory activities that include large or small group discussions or individual learning. There may also be an opportunity for personal reflection around what’s being taught, and the opportunity to discuss it in a small group. A teacher or other group leader may put those findings on a whiteboard, and give the greater class the chance to talk about all those different perspectives.

These examples of multi-sensory learning offer students as many ways as possible to engage with the material.

Why student autonomy is important

But what if you’re in a lecture-only class and aren’t experiencing those multi-sensory activities mentioned above? A student’s ability to learn the class material shouldn’t be left solely to how the teacher teaches it. Instead, students should take control of their own learning experience.

“The storyline is definitely autonomy,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “Students have to become much more autonomous in their learning and they need to become way more autonomous in how they assess themselves.”

In this case, students may need to create multi-sensory opportunities for themselves to make what they’ve learned “stick,” based on the kind of activity that works best for them — like certain kinds of note-taking, practice testing, or teaching others.

How to make learning applicable and personal

The best way to retain what you’ve learned is to make what you’re learning applicable to your life and personal to you.

For example, reading Shakespeare may seem foreign to you, but you may find that the characters’ passions and challenges are very relatable to your life. Or, if learning history seems boring, look for cultural or societal implications that may inform your understanding of the same thing today.

“It’s the same concept, but you reach it in different pathways in the brain,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “So if you’re able to help yourself find that personal connection, you enhance the probability that you’re going to be able to recall it.”

5 Active Learning Techniques You Can Use Today

“All learning depends on well-functioning memory systems and well-functioning attention systems,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “So anything you do that enhances memory or intention is going to enhance the likelihood of learning.”

How can you take the lead on your own learning and increase the chances of retaining what you read, discuss, or hear in class? Here are some best practices and techniques you can implement today.

1. Spaced repetition

Spaced repetition is the practice of reviewing what you’ve learned at certain intervals, which reinforces the concepts in your brain and deepens those neural pathways.

“When you rehearse, you enhance the speed with which recall occurs because you enhance the myelin sheath, the electrical signal goes faster, and you’re able to apply the information,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. She also advises that the more complex the concept, the longer the time between repetitions should be.

2. Practice tests and low-stakes testing

Students can use practice testing to reinforce concepts as well, whether it be in a structured environment or on their own with pre-made practice tests. Students can even make up their own tests by asking themselves what their teacher would likely put on a test, and then answering those questions.

Low-stakes testing can simply be a quiz on material just recently learned to reinforce core concepts and knowledge.

3. Teaching others

Another way to test your retention or to practice what you’ve learned is to teach it to others. This requires you to know the concept well enough to articulate it in your own words. Practice teaching your newly-acquired knowledge to others through a formal presentation in class or through an exercise while studying with friends or alone.

4. Active note-taking

If you want to better track and reinforce the concepts you learn in class, consider taking a more active approach to your note-taking skills. Some types of different note-taking include:

- Cornell Notes: This approach lets you see higher-level concepts by writing questions, connections, and patterns next to your detailed notes.

- Outlining: Take notes by turning class information into an outline, with headers, subheaders, and bullet points.

- Mapping: Create a map of the concepts from class and how they relate to one another.

- Sentence Notes: Write one sentence per each key point you want to remember.

Of course, the best note-taking system is the one that works best for you (and you can learn more at Harvard’s Academic Resource Center “Note-Taking” resource).

5. Receiving and applying feedback

Another active learning technique is to listen to the feedback you receive and apply it to future assignments. Instead of being interpreted as something negative, feedback — or “feed-forward,” as Tokuhama-Espinosa calls it — is a way to look at your current process and ask what you could do differently the next time.

“One of the best ways to learn is to take the time to assess what you didn’t do, or where you didn’t spend time,” she says.

What is the Best Environment for Learning Retention?

In addition to the approaches above, learning is best done in the right environment. But the right environment for you may be different than the right environment for others.

Tokuhama-Espinosa explains that when first asked about their ideal learning environment, students often say they learn best after having a cup of coffee, after a workout, or in a quiet place.

However, after learning more about their unique learning styles, students come to realize that their best learning is done by listening to other people’s perspectives on the same topic, taking notes by hand, or through other more active approaches.

“Sometimes you need to be in a loud, noisy space and do your work and feel like you’re part of something. Other times, you need to be quiet. And that’s okay,” says Tokuhama-Espinosa. “Different people need different things at different times to reach the same goal. So know yourself better. I think that’s the key.”